Read the transcript >

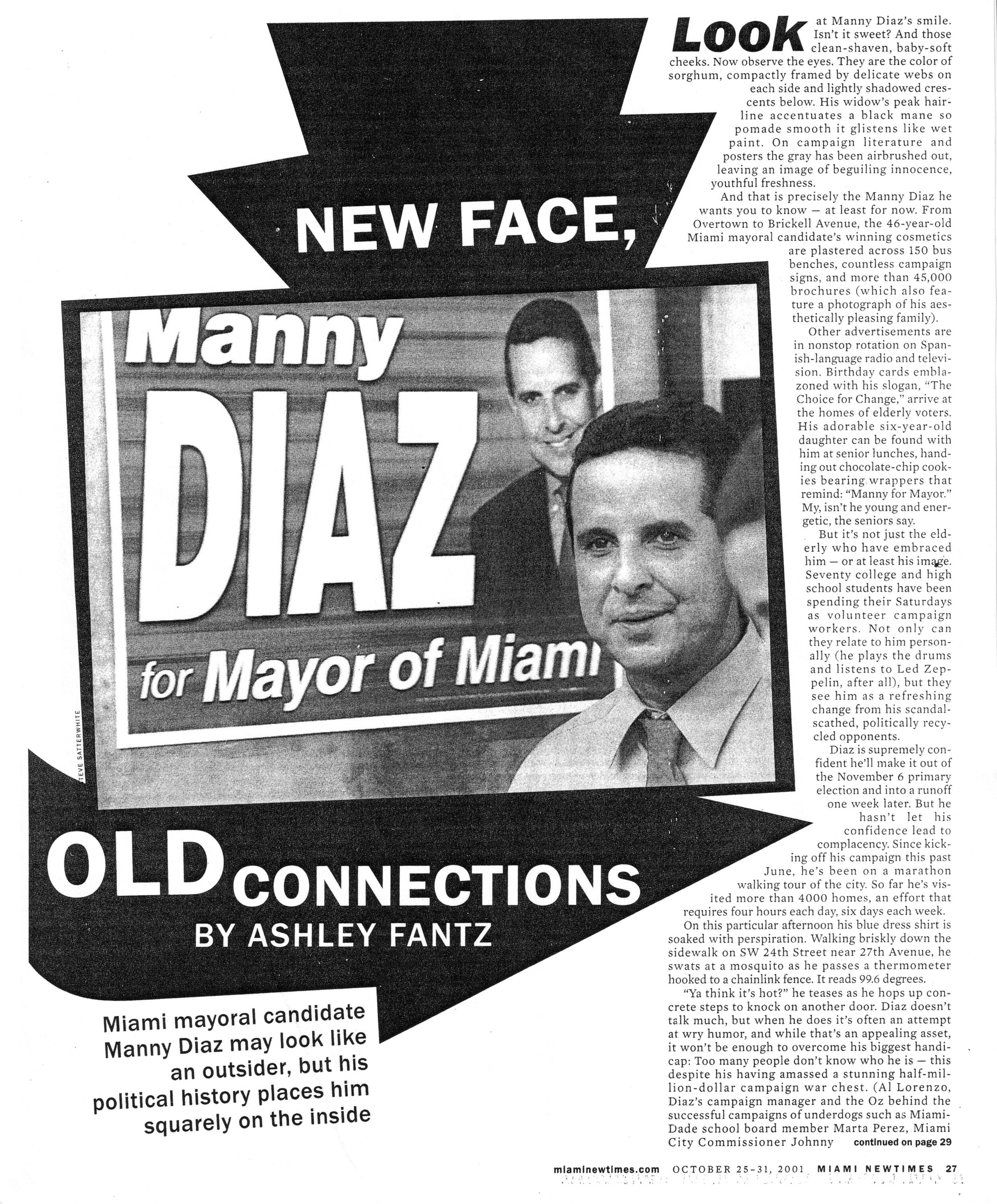

Look at Manny Diaz's smile. Isn't it sweet? And those clean-shaven, baby-soft cheeks. Now observe the eyes. They are the color of sorghum, compactly framed by delicate webs on each side and lightly shadowed crescents below. His widow's peak hair-line accentuates a black mane so pomade smooth it glistens like wet paint. On campaign literature and posters the gray has been airbrushed out, leaving an image of beguiling innocence, youthful freshness.

And that is precisely the Manny Diaz he wants you to know — at least for now. From Overtown to Brickell Avenue, the 46-year-old Miami mayoral candidate's winning cosmetics are plastered across 150 bus benches, countless campaign signs, and more than 45,000 brochures (which also feature a photograph of his aesthetically pleasing family).

Other advertisements are in nonstop rotation on Spanish-language radio and television. Birthday cards emblazoned with his slogan, "The Choice for Change," arrive at the homes of elderly voters. His adorable six-year-old daughter can be found with him at senior lunches, handing out chocolate-chip cookies bearing wrappers that remind: "Manny for Mayor." My, isn't he young and energetic, the seniors say.

But it's not just the elderly who have embraced him — or at least his image. Seventy college and high school students have been spending their Saturdays as volunteer campaign workers. Not only can they relate to him personally (he plays the drums and listens to Led Zeppelin, after all), but they see him as a refreshing change from his scandal-scathed, politically recycled opponents.

Diaz is supremely confident he'll make it out of the November 6 primary election and into a runoff one week later. But he hasn't let his confidence lead to complacency. Since kicking off his campaign this past June, he's been on a marathon walking tour of the city. So far he's visited more than 4000 homes, an effort that requires four hours each day, six days each week. On this particular afternoon, his blue dress shirt is soaked with perspiration. Walking briskly down the sidewalk on SW 24th Street near 27th Avenue, he swats at a mosquito as he passes a thermometer hooked to a chainlink fence. It reads 99.6 degrees.

"Ya think it's hot?" he teases as he hops up concrete steps to knock on another door. Diaz doesn't talk much, but when he does it's often an attempt at wry humor, and while that's an appealing asset, it won't be enough to overcome his biggest handi-cap: Too many people don't know who he is — this despite his having amassed a stunning half-mil-lion-dollar campaign war chest. (Al Lorenzo, Diaz's campaign manager and the Oz behind the successful campaigns of underdogs such as Miami-Dade school board member Marta Perez, Miami City Commissioner Johnny Winton, and a bevy of state legislators, says underestimating Diaz is like underestimating the Karate Kid. "He's washing the car, catching flies with chopsticks to get ready," Lorenzo says as he raises his arms and knee in imitation of the famous Karate Kid stand. "He's just waiting, you know. And then, whammo! It's going to be all over with.")

The candidate leans forward to ring the doorbell. Gladys Saez appears. Her eyes open wide and she covers her mouth with both hands, as though she's just won a sweepstakes. ";Yo se quien to eres! [I know who you are!]" she exclaims. "Tu eres el que cuidci al nitio. [You're the one who took care of the little boy.]" Saez has recognized Diaz not from his bus-bench ads or direct-mail brochures but because he was one of Elian Gonzalez's most visible lawyers. Saez has a celebrity standing on her doorstep.

She ushers him into her kitchen and brews him Cuban coffee. They chat for fifteen minutes about her family and the weather but don't discuss the election. She doesn't ask about issues. Disappear-ing into another room, she returns with a cordless phone. "Guess who's in my kitchen?" she brags to a friend. The candidate's eyebrows jump as he sips a glass of water. Another vote?

People don't tend to dive behind their couches when Manny Diaz raps at their door. Even in Miami's predominantly black neighborhoods, where Diaz's efforts on behalf of Elian were decidedly unpopular, he is greeted politely if not enthusiastically. And though he repeats often that his campaign has nothing to do with the Cuban boy, he isn't foolish enough to fight his double-edged celebrity, even if that means tolerating the occasional resident who mistakes him for Jose Garcia-Pedrosa, another Elian attorney-turned-mayoral candidate.

"He's not unknown in political circles, but voters don't really know him," says pollster Sergio Bendixen, whose June survey ranked Diaz dead last in every category, including name recognition. "Manny is in a great position, though. He has no negatives, which is more than Carollo and Suarez can say, and he can mold public opinion of himself."

But there remains another obstacle for Diaz, and it's a big one. "Manny's gotten off to a slow start with his platform," explains Bendixen. "I've heard him say he wants to be the mayor in a very general way that's almost slogan-like. For a new candidate, having a clear reason for running apart from just being new is crucial. We need to hear what he stands for, who he is, what kind of vision he has for the city. Who is Manny Diaz?"

The odor of cigarette smoke hangs in Diaz's Coconut Grove law office. Sunlight pours through bay windows and splashes across bare walls he hasn't had time in four years to decorate. His wood desk is bare except for a pile of papers stacked neatly in one corner. An oversize ashtray sits next to his computer. "I can't seem to quit," he confides referring to the Salems he's smoked since he was a teenager. "And now probably would not be the best time anyway." Still clocking twelve-hour days at his civil practice -Diaz & O'Naghten — Diaz begins work at 6:30 a.m., mak-ing phone calls to potential campaign contributors. Afte• pushing his campaign int,o overdrive in midsummer, he taken on very few cases unusual for an attorney accu come to juggling many.

Colleagues describe him obsessively organized a claim he maintains a filing system that rivals the Pentagon His wife, Robin, adds that; not an "at home by 6:00" 11 of guy. In fact, his manic ‘k habits commonly cause him to lose weight and sleep when he's involved with something important. At the height ae Elian saga, he dropped fifteen pounds and pulled all-nighters one after another. Longtime friends know him as a line overachiever. Remember the kid in high school was president of the senior class and the student council? The one who got the girls, scored the touchdowns, made good grades, and had perfect skin? Well, he's grown up now, and he's running for mayor.

Born in Havana on November 5, 1954, Diaz was reared by his homemaker mother, Elisa, and strict father, Manolo, an orphan educated in Fulgencio Batista's military schools. After moving to Miami in 1961, Diaz attended Belen Jesuit Preparatory School, regarded as a veritable incubator for future leaders. There he became the "MVP of everything," recalls classmate Carlos McDonald, now an aide to Florida Attorney General Bob Butterworth (also a Diaz supporter). "Manny was class president, president of the student council, a great athlete," says McDonald. "He was a popular kid. I think we all just assumed he would run for something someday."

Diaz was on track to fulfill Belen's traditionally high expectations by receiving a scholarship to Columbia University. But the eighteen-year-old's academic dreams were dashed when he got his high school sweetheart pregnant. "It was definitely a surprise," he remembers, "but I loved her and I thought it would work. Family has always come first for me. My parents were supportive. We had to deal with what life had handed us." He gave up Columbia and went to Miami-Dade Community College instead. "Not to disparage Miami-Dade," he says, "but I felt like I had worked hard and that I would go Ivy. But you just have to remain who you are and stay committed to family." He and his new wife Patricia McNamara struggled to raise Manny Jr., now a 27-year-old assistant football coach at North Carolina State University. The young couple lived in a small Miami Beach guest house that McNamara's father, a real estate businessman, loaned them.

While she earned a nursing degree, he took care of the baby, went to school part-time, and worked for the National Enquirer. "I had to get a job, and that's what I could find. I would go to Eckerd and count all the magazines in the rack and make an X on each one," he says, laughing at the memory. "Those were desperate days."

By the time he graduated from MDCC, he and his wife had amicably split. She took Manny Jr. and he took out more school loans, enrolling at Florida International University and graduating with a degree in political science. Immediately he went to University of Miami's School of Law. He helped his parents buy a new house with a bonus he received from his first job as an attorney.

Diaz's motivation in running for mayor is intertwined with his father's death in 1999. Manolo Diaz, beloved in Miami's Cuban community for his exuberant sense of humor and love of baseball, instilled in his son an appreciation for activism. "When I was six my father organized a strike in his electrical union against Castro and was sent to jail for about a year," he recounts. "I remember that I was outside playing one day and there were some announcements over the radio that they had shot prisoners along the wall.' All of a sud-den adults came rushing out into the yard crying. So the kids started crying. Apparently they had announced that 'Manny Diaz' had been shot, which we assumed was my father. We lived daily with the fear that my father wasn't coming back, and I began to understand what it meant for politics to become like breathing, for your life to depend on how strong and honorable your government is."

His father's death had a profound effect on him. "I felt a void in my life," he says. "I looked around the city, to the place where my parents had invested their dreams. It felt different, like someone had over the years taken something from it. People have forgotten what I knew growing up here. Neighbor-hoods are the heart of a city. There's a woman who couldn't get out of her apartment for three days because of flooding, elderly people who don't have furniture or air conditioning; people won't leave their homes at night for fear of being a crime victim. The streets are torn up, garbage isn't picked up on time."

His brooding has coalesced into something that resembles a political platform, albeit a pretty straightforward one: neighborhood improvement. Generally blaming Miami's past leaders for "building skyscrapers but ignoring people," Diaz wants closer scrutiny of how the city spends millions it receives from the federal government for rehabilitating distressed neighborhoods. He plans to provide financial incentives for tightly focused projects on targeted streets. Civic and business leaders, he says, have pledged their assistance in hosting workshops for start-up entrepreneurs.

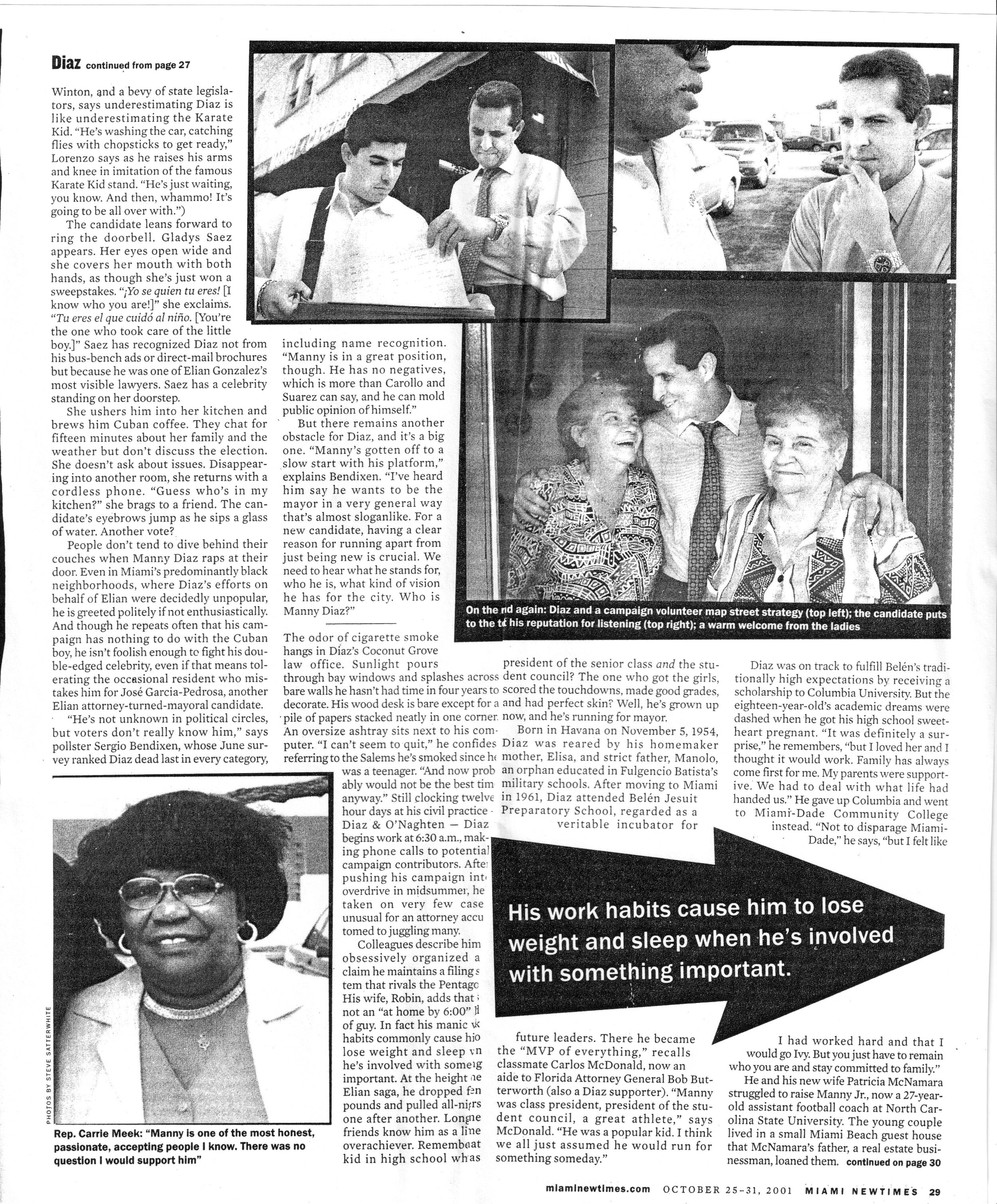

Many of the candidate's ideas about rebuilding Miami's poorer areas come from U.S. Rep. Carrie Meek, who has endorsed Diaz in a mailing sent to 9000 black and Haitian voters. Considering Meek's impressive pull in those communities, her endorsement is a major coup. "Manny is one of the most honest, passionate, accepting people I know. There was no question I would support him," says Meek, noting that her friendship with Diaz stretches back more than twenty years, when he helped her campaign for the Florida House of Representatives.

"He sat down with me and listened to what I thought should be done in black neighborhoods," she goes on. "That's one his best attributes: He listens to people, then thinks, then acts. I've seen him be fair with all people. He's passionate, concerned about economic development. He promised me he would focus on the inner city."

Promises are fine, says Bishop Victor Curry, but black Miamians are skeptical. The influential pastor of New Birth Baptist Church, Curry also is the popular host of a radio talk show on the church's station (WMBM-AM 1490) and former president of the NAACP's Miami-Dade chapter. He issues a warning about promises: "We've heard too many of those. This year it's all about your record. We don't have problems with Manny because of Elian. Elian has nothing to do with our future. Do the things in Mr. Diaz's past suggest that he would support the citizen review panel [to oversee the city's police depart-ment]? Would he be sensitive to the poorer areas of the city that have gone for decades without attention?" In a mailing directed at black and Haitian voters, Diaz has pledged his support for the review panel, which will come before voters November 6. The letter, though, does not spell out his reservations. "I'm definitely for it," he explains, "but I'm concerned about the timing — like if it's going to interfere or hamper police investigations. I don't know if I agree that police should-n't participate [on the panel]."

Just a year after graduating from law school, 25-year-old Diaz, known in local political circles for his work on Meek's campaign, was asked to lead a newly formed organization called SALAD (Spanish American League Against Dis-crimination). Initially reluctant, he feared the post would disrupt his law career and cast a constant political spot-light on him. "When I was still in school, I got to know local politicians, and the one thing that stuck out was their personal and business lives were a mess," he recalls. "I didn't want to go through that. Then Mariel happened."

In April 1980 Fidel Castro opened the Cuban port of Mariel and allowed nearly 125,000 Cubans, many of them criminals or mental patients, to immigrate to the United States. According to the State Department, approximately 90,000 settled in South Florida. Nearly all were protected from deportation by the special status afforded Cuban immigrants by federal law.

Similar protections, however, were not extended to Haitian immigrants, several thousand of whom were deported between 1980 and 1984 under orders of the Reagan administration. Diaz opposed what he perceived to be a double standard, and as leader of SALAD (he had overcome his reservations), he coordinated with attorneys around the nation to help Haitian refugees obtain legal advice, encouraged people to pressure public officials, and led a lobbying effort to introduce legislation that would make immigration laws more evenhanded.

Although that was more than two decades ago, stresses his Mariel position in campaign ads and has reminded key Haitian, Cuban, and black leaders of it. "Manny showed me a newspaper article from that era," says state Rep. Phillip Brutus, the first Haitian to be elected to Florida's legislature. "Mariel meant to me that he had enough guts to say what he felt, when he didn't have anything to gain; he wasn't running for office. I just couldn't [endorse] anyone else."

In 1981 Diaz marched SALAD into another high-profile battle, this time against Citizens of Dade United, a predominantly Anglo group that successfully introduced a referendum (passed by 60 percent of voters) prohibiting the county from conducting business in any Ianguage other than English. In the press Diaz blasted it as "ridiculous, petty, and senseless." The county, exploiting the ordinance's broad language, continued to provide emergency, medical, tourism, and other services in Spanish. "It was a disgusting display of bigotry," Diaz remembers. "The beginning of the Eighties was really tense in Miami. You think there's some distrust now between differ-ent groups? Back then it was unreal."

Gaining confidence, Diaz was becoming an effective rhetorical machine gun, strafing any group that appeared exclusionary. In 1983 he unloaded on Miami Beach Mayor Norman Ciment for suggesting that the city erect roadblocks to keep foreign immigrants from moving to the Beach. Diaz told the Miami Herald that Ciment's suggestion was "the most appalling and irresponsible statement ... from a public official in a long time." A month later Diaz grilled the Burger King corporation for a memo it sent to its Miami restaurants forbid-ding work-related discussions in Span-ish. If the policy wasn't changed, Diaz announced, Hispanics would have it their way — at McDonald's. The chain quickly retracted the ban.

Diaz then took aim at an old-line Miami institution, the Orange Bowl Committee, for rejecting membership applications from a black, a woman, and two His-panics. Next he aligned SALAD with the Dade Hispanic Officers Association, which had filed a complaint against the Miami Police Department for not hiring or promoting enough Hispanics.

In 1984 Diaz stood before a gathering of the county's elected officials and political activists and turned what was expected to be an inconsequential luncheon speech into a full-throttle assault on Cuban-American Republican campaign strategies that pandered to Hispanic voters. In the same diatribe, he ripped Anglo Democrats for not encouraging Hispanic Democrats to run for office. Although he resigned from SALAD in 1985 to concentrate on his law career, Diaz couldn't bring himself to completely leave the political arena. In fact he immediately began helping Bob Butterworth raise money and garner voters for his first run for attorney general in 1986. "Manny was a force," remembers Butterworth. "He helped me from the beginning. He's not just a guy coming out of nowhere. He knows politics and would, considering the competition in that race, make a great mayor for Miami." (The attorney general has contributed $1500 to Diaz on behalf of himself, his wife, and her business.)

Asking people for money may not be something Diaz relishes, but he has been exceedingly successful at it. As of September 30, the latest date for filing campaign reports, he'd received $530,785. Attorneys and insurance industry insiders have been the biggest givers. "I just picked up the phone and called a few friends," he shrugs. Among those friends is U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson, for whom Diaz raised money when Nelson was elected state insurance commissioner in 1994 and 1998. In turn Nelson appointed Diaz to the Florida Joint Underwriting Association, the state insurance pool, where he established contacts that have paid off in his bid for mayor.

Nelson introduced Diaz to a range of Tallahassee movers and shakers, people who today are bringing him both campaign contributions and criticism. "I don't know how you can say you're new when all you've got around you supporting you are these people who've played the political game for a long time," says mayOral opponent Jose Garcia-Pedrosa. "These people will eventually want a payback."

Long-time Miami political consultant Ric Katz says that kind of carping is unfair. "If you're mostly unknown, you have to raise substantial money to buy media," he notes. "You take a certain amount of hits for it, but that's insider politics that the public rarely grasps."

As of last week Diaz had not contributed one dollar of his own money to the campaign. He hasn't needed to. Not that he doesn't have the means. He estimates his net worth at between two and three million dollars, most of which was amassed while working as chief counsel at Terremark, Inc., a Coconut Grove develOpment company. During the mid-Eighties Terremark, headed by entrepreneur Manny Medina, was flying high. Flush with success and eager to extend his reach, Medina in 1986 purchased Monty's Bayshore Restaurant in Coconut Grove from its namesake owner, Monty Trainer. (Diaz represented Medina in the deal.) Monty's, which sits on city-owned waterfront land, was a historic watering hole for Miami's power elite. Thanks to Trainer, it also was steeped in controversy. Many people thought Trainer's lease agreement with the city was a sweetheart deal, a perception that seemed to be confirmed by city auditors, who accused him of bilking taxpayers out of nearly $200,000.

(Trainer eventually went to federal prison after being convicted of tax evasion.) When Medina's real estate empire began to crumble in early 1991, he sub-leased the restaurant and adjoining shops to Manny Diaz and political insider Stephen Kneapler. Today Diaz owns fifteen percent of the operation, which now includes a Monty's restaurant in Miami Beach. He says his annual income from the Monty's businesses and his law practice totals $500,000. Despite the potential for conflicts of interest should he become mayor, Diaz says he does not intend to sell his interest in Monty's in the Grove.

But the appearance of a conflict could present dangers, a possibility already anticipated by campaign manager Al Lorenzo. "I call them UFO's — unidenti-fied flyers," Lorenzo says. "The other guys will put them out linking Manny to Monty, Manny to anything to make him look bad. But they are completely stupid if they think that Manny's part-ownership of one of the most profitable, popular restaurants in town is going to look bad."

Ric Katz agrees. "Guilt by association usually backfires," he warns. "I don't know whether the other candidates are going to exploit that. My guess is that someone probably will."

Two weeks after the terrorist attacks, while America was still hard-wired to 24-hour news coverage, Lorenzo sat at Versailles restaurant. Prior to the assaults, he explained as he doodled on a paper place-mat, the plan had been to purchase lots of media, including billboards, in the closing weeks. But media is expensive, and contributions dropped off dramatically after September 11. Predictions of raising a million dollars by the end of October vanished; the campaign will probably be lucky to reach $700,000. (As of September 30, Maurice Ferro had raised $343,000, Willy Gort $231,000, and Joe Carollo $226,000.

The other candidates — Xavier Suarez, Jose Garcia-Pedrosa, Emiliano Antunez, Danny Couch, and Miguel Alfonso — trailed far behind.) "Let's say I go full-court press and buy all the television airtime I can," he said, sketching a basketball court on the place-mat. "Then we start dropping bombs, and the news dominates."

Lorenzo's prescience has offered little comfort. The proven efficacy of broadcast media has been upended. One thing, though, remains certain: His candidate must continue walking the neighborhoods, knocking on doors, visiting senior centers, and reminding voters who has endorsed him. (On October 8 he added the Miami gay-rights group SAVE Dade to his list.)

A recent Miami Herald/Univision poll provides hope. It showed that Diaz would be among the top three vote-getters on November 6. In a runoff against Carollo, Diaz would waltz to victory. "A lot of time was wasted talking about me in terms of the [earlier] Bendixen poll and how poorly I registered," Diaz says. "What a difference a few months make. People are listening to me, getting behind me. Ferro and Carollo can talk, talk, talk. But change is going to happen. I promise you."